Short Story

by J.T. Aris

There is a well in every village in Denmark; there has to be. Even if water can be brought from a nearby river, creek, or stream, the village ends up with a well sooner or later. Some wells are ornate, while others are but a simple hole in the ground with nothing but a bundle of mismatched sticks stuck into the earth around it to keep wayward animals or children from falling in. Some are new, and some are too old for anyone to remember who put them there. Some wells, they say, are older than the village itself.

The well in the town I grew up in was one of these. It lay in the very center of a grove of trees, brimming with fresh water and surrounded by good dark earth that sprouted the greenest seedlings in the spring. It was once crude, made up of nothing but that simple dirt, just like the paths worn into the grass by people trekking to and fro with empty and then filled buckets.

Over time, the people built a village around the well. Trees were felled to make room, and farmland was tilled. Huts, and then houses sprang up, radiating outwards like a fairy ring of mushrooms from that one central point. The worn dirt paths became cobbled roads, and stones were set into the wet earth of the well and built up around it in a perfect smooth circle. A sturdy pair of wooden posts were erected at opposing sides of its diameter; a rope and pulley rigged from the central beam to dangle a pail over the hole’s dark depths.

Even during the hottest summers, the well’s bucket would return from its seemingly endless plummet, filled with cold, clear water. The rope sometimes had to be lengthened, but there was always water to be found just a little further down. The well never ran dry, and the town prospered.

My family’s small goat farm was built upon one of the plots furthest from the well. I was the oldest daughter in my family, the middle child, not yet strong enough to till the field with my older brother and father, nor was I nimble enough to be trusted with needles or hot things in the kitchen.

Instead, I tended to the goats. I fed them, milked them, led them out to pasture and shooed them back inside the barn before dark. When their trough ran dry from lack of rain, it fell to me to fetch water from the well. I would hitch up the strongest nanny goat to a small cart made of half a barrel, cut lengthwise from top to bottom and affixed to wheels, and drive it into town. I could ride in the barrel when it was empty, pretending I was Thor driving Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr into battle and making the thunder all along the way. I would arrive at the well, climb up onto the stone wall, kick the bucket in, and listen to it fall down into the dark with a satisfying splash. All that remained was to crank it back up as many times as I needed to fill the trough. No one ever minded me, no matter how much water I took or spilled. The well never ran dry.

Sometimes I would see old Fru Jytte, the wise woman, on my way to fetch water from the well. She would come hobbling up to its stony edge, a gold coin gleaming in her gnarled fingers. The sight of the shining trinket would call all the children within sprinting distance immediately to her side. They, myself included, would stand politely around her, hands clasped behind our backs and make utter sycophants of ourselves in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, she would gift one of us with the coin this time.

“Hello Fru Jytte, can we help you?”

“Do you need water?”

“May I draw it up for you?”

“I can carry it for you, Fru Jytte?”

But she would wave all of us out of the way irritably, and toss the shining gold directly into the well. We children would rush to the stone wall’s side, watching the coin fall, hearing it clink enticingly against the stones, and wait for the inevitable little plop at the end. More than one of us let out a wistful sigh. Fru Jytte would take no notice. She would already be halfway back to her cottage by then.

One of the boys, Peter, insisted that the bottom of the well was covered in gold coins, and that, if the water ever sank low enough, one of us could drop the bucket and heave it back up full of gold instead of water. We did once conspire to lower my younger brother down into the well to have a look, but Jytte caught us just as we had coaxed little Leif into the bucket. Fru Jytte took me harshly by the ear and gave Peter such a lussing that his cheek was pink for two days after. She gave us all a look so stern it would have shamed Odin himself, and the children scattered. Fru Jytte returned my brother and me to my mother, but strangely did not tell her what I had done. I did not so much as think to lower my brother or anyone else into the well again after that.

Until, one winter, just as I was turning twelve, old Fru Jytte took ill. She was ill for a month. Many of the other children speculated that she had died, but I disagreed. I was fairly certain Fru Jytte was immortal, a witch, Freya in disguise…or perhaps Loki.

The adults took turns to look in on her. They all left the cottage muttering and shaking their heads. On the 31st day, a priest was called. The adults stopped visiting Fru Jytte after that.

The winter grew colder and the well… ran dry.

At first, we thought it had simply frozen over. Two of the strongest men in the village took turns throwing huge stones forcefully down into the well as the rest of us stood around its lip, listening intently for any sound of breaking ice or a splash of water. The hope died repeatedly with each dull, dry thud. The well’s bucket always came up empty. Everyone went home, not talking. Not even whispering. Every adult had the same faraway look on their faces.

My mother and father started carefully melting snow over fires to cook and to wash. We kept the goats in to keep them from trampling the now precious snow. We brushed it from the thatched roof and carried it inside with frostbitten and trembling fingers.

A small huddle of people stood around the well every morning, stamping slightly to banish the cold from their toes or blowing on their hands. All waited, hoped, and watched as each day someone new dropped the bucket into the well and cranked it back up. Fewer people showed up at the well each morning. The rope had been lengthened twice and still there was no sign of water, or even the bottom of the well.

Within a fortnight, only we children were still performing the daily ritual. We took turns. One would turn the crank. Another would lean over the stone wall to peer down into the dark for the returning bucket, ready to call out at the slightest gleam of water.

“We need gold,” Anna, Peter’s sister, announced one day when our much smaller crowd of children had gathered around the empty well. “Maybe the well needs gold to make water. You remember Fru Jytte always threw money into it before she died.”

This was a point we all agreed upon. Though, none of us had any gold to offer to the well.

“We’ll borrow some from our parents. Find old gold jewelry no one will miss and throw it in,” said Peter.

I punched Peter in the arm and snorted. “That’s a dumb thing to do! What if it doesn’t work? How would we get it back? That’s not borrowing! That’s stealing!”

Anna shrugged. “If it brings back water, I’m sure our families won’t mind.”

“Or we lose my grandmother’s gold necklace and my father throws me down the well after it,” I sniffed. The other children turned to look at me, suddenly and horrifically inspired.

I was no coward, so the next day, my pockets heavy with every gold ring and necklace we could find, I climbed carefully onto the well bucket. I hugged the rope with my arms and knees. My feet trembled slightly where they balanced on the old bucket’s cracked, wooden rim. The pulley creaked and squeaked as I was slowly lowered down. The small candle I carried sputtered, the bucket swaying as I slowly dropped beneath the rim of the well. The flame grew still, casting a pale glow on the old dry stones as I was lowered down further and further and further.

When the opening of the well had shrunk to a small bright circle above me, a chill gripped my stomach. It was impossibly dark, my shrinking candle hardly seeming to pierce the blackness at all. The flame flickered as my hands shook.

After what felt like hours, the rope stopped with a jerk. I was at the end of it, dangling in the darkness. I could hear something dripping. The air was somehow colder down here, but unmistakably moist, thick. I swallowed hard around it, venturing to squat down a little to try to make out the bottom below. I carefully wrapped one arm around the rope and lowered the candle down with the other. The walls were a dark clay that did little to help me distinguish them from anything else. They shone wetly in the weak light from the stub of my candle. I wondered for a brief moment if I should be brave and simply let go. The dripping sounded like it was collecting below me. Fairly close by...

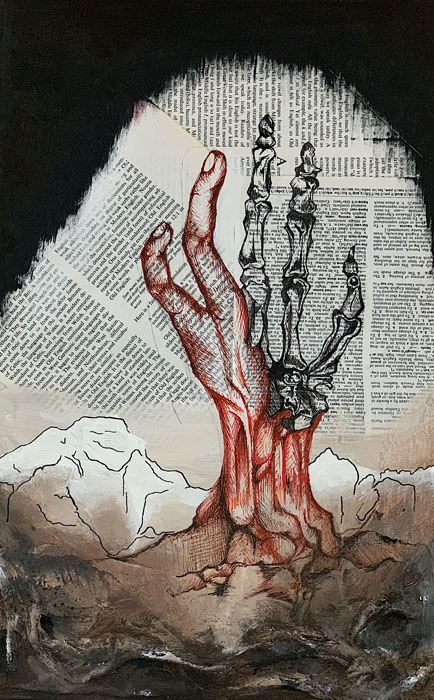

I was experimenting with the idea of taking one foot off the bucket to dangle it lower, when I realized that I was not the only one down at the bottom of the well.

A fierce cold chill ran the entire length of my spine, leaving me gasping and shaking worse than ever. There was a shape across from me, a slightly oblong head bowed on a too scrawny neck. A pair of thin but muscular shoulders melting into the darkness below. They rose and fell gently with a soft rasping sound. I was about to scream, but managed to choke it down. Whatever this monster was, it seemed to be asleep. I was entirely sure that waking it would be the very worst thing I could do. I took three slow and careful breaths, and then tried to gently tug at the rope as a signal for the others to pull me back up. If they were still up there. The mouth of the well looked so impossibly small. I felt as though I hung there for hours. When I dared to glance back at the creature again, it was looking at me.

Its eyes were huge and red, cold and calculating. It never blinked, only stared up at me from a shrunken, wrinkled face. Its bruised lips parted in a lopsided smile filled with an array of sharp, snaggled teeth. It raised a long-fingered hand, and waved at me.

“Hej…” the monster hissed in a wet and gasping voice like someone sick.

“Hej,” I whispered back, feeling tears well in my eyes.

It asked me what I was doing all the way down here.

“Looking for the water,” I answered, my heart pounding as my bucket swayed just a little closer to the monster.

It smiled, and the smile was horrible as it stretched the confines of the creature’s face. I wondered if that mouth could simply stretch forever and swallow me whole.

“I har ikke betalt…” it hissed, the spidery hand returning with two gold pieces in its fingers. It let them fall, and they seemed to take an awfully long time to clatter to the bottom.

I swallowed and nodded. “I was sent here to pay you. For the water.”

I had to hold myself rather precariously to dig around in my pocket. I held up a handful of the stolen gold rings. “Are these enough?”

The creature gave a phlegmatic cough which might have been a laugh.

“More than that,” it gargled. “You are very behind in your payments to your Brønmand…”

I had the sickening realization that the monster must have been only sitting before as he suddenly stretched, now at eye level with me, proffering a hand. It was dark and slick, clammy, and smelled like rot. I tried to drop the gold into the Wellman’s palm, but he closed it before I could and pointed down towards the well’s bottom instead. I tossed the gold into the well and dug in my pockets for more.

“I-is that enough?” I asked, shivering and dreadfully conscious that my pockets were now empty.

“For water? Yes. For your life?” The Wellman smiled horrendously. “You did not mention that as part of the transaction.”

I hugged the rope tight, my heart racing. I glanced desperately at the well’s opening above me, wondering if I could inch my way back up the rope.

“Y-you have all this gold,” I stammered. “You could buy anything you wanted! A chicken or a goat or a nice fat pig to eat! You don’t want me!”

The Wellman only chuckled and batted lazily at the bottom of my bucket with those long, rotted fingers. It swayed worryingly and I hugged the rope tighter. I started to try to inch up it, the rough cord scratching my skin.

“Why buy something when I can have a fresh little girl for free? Anything that falls into the well belongs to me,” he gurgled, still grinning as I struggled to climb up the rope.

“I-if you eat me, you’ll break the rules! I haven’t fallen in!” I sobbed.

“Not yet…”

“Who would pay you if you keep me here? People are moving away now that the well is dry, you’ll be all alone soon!”

The Brønmand paused for a moment, those red eyes widening. “New people will come. People will always need water.”

“But who would tell them where the water comes from? What to do? How to pay you?” I gasped, still climbing doggedly upwards. The top of the well was so far away. My cold aching fingers slipped, and I cried out as I slid back down with a lurch, the bucket swinging wildly. I squeezed my eyes shut and clung on for my life. I felt the Wellman’s breath as the bucket swung closer to his face.

The Wellman hissed, thoughtfully, as I dangled before him. Then, he offered me a bargain. Foolishly, I took it and was permitted to escape. His red eyes peered up at me through the darkness, watching me all the while I was drawn up from the well, water dripping from the bucket beneath me once again.

Early in the mornings, or late in the evenings when I could slip away without being noticed, I brought the Wellman his payment of blood rather than gold. Twice a month I flung some poor wretched creature into the well. I started small. Rats and mice and chipmunks. Then chickens. One time I even offered a newborn baby goat while I sobbed my eyes out. I could feel the Wellman getting hungrier, but I had to keep it sated, gorged, or the Wellman would crawl out of his dark den and find me or my friends. I was sure of it. Whenever I woke from a nightmare full of long slithering arms and glowing red eyes, I knew the Wellman needed feeding.

The water was never quite so cold or so clear again. It took on a tinny metallic taste and an unpleasant tepid warmth. People in my village seemed angrier, more brutal to one another. The crops struggled to grow even when given plenty of water. The grass creeping up around the stones of the well died, and it did not take long for the villagers to begin speaking of curses and witches.

A priest was called to cleanse the well of evil spirits. The remaining villagers gathered, myself included, to watch. But all his emphatic and heartfelt words and pleas to God did nothing. When the priest lowered the bucket with his fine golden crucifix into the well, it returned with a drowned blackbird floating alongside it, eyes glassy black, blood trailing from its beak.

Every last one of the Danes in that village fled, leaving nothing but empty houses spiraling out from the cursed well.

My family moved away, crossed the sea to the small islands to the north, as far as my parents would take me. I feared how long the arms of a blood-fed Brønmand could stretch. My dreams grew worse and worse. I had them almost nightly, feeling those gnashing teeth an inch from my throat, those long dark arms reaching and growing like evening shadows to drag me down to glowing red eyes. I heard the terrible garbled voice cursing me, laughing at me, whispering the names of all the people the Wellman would devour because of my broken promise. I saw them. Bloated, drowned, and staring before being swallowed whole by the shadowy creature.

But then one day the nightmares stopped, and I hoped the Wellman had starved and died with no one left to pay him in gold or blood. I grew older, was given my own goats, built a small cabin, and managed to forget the terrible things I had done. Perhaps I had even imagined it all. Children’s memories are so often warped by stories.

But last night, I awoke in a cold and clammy sweat. I saw the Wellman once again, peering at me with those red glaring eyes, that terrible grin, and those long dark arms spilling over the well’s sides and slithering out, reaching for me. The lip of the well became the foot of my bed and those rotted wet hands closed on my ankles to drag me back down into his dark, cold throat. Should you see a Wellman in your dreams tonight, I hope you remember to pay in gold.

Appeared in Issue Spring '21

Nationality: Danish

First Language(s): Danish

Second Language(s):

English

Das Land Steiermark

Listen to J.T. Aris reading "The Wellman".

Supported by: