Published July 3rd, 2023

Review

by Viviana De Cecco

Maps for Lost Lovers (2004) is a complex book, exploring themes such as freedom and oppression, love and loneliness, religion, racism, legal and illegal immigration, and conflicts between parents and children. Describing the difficult coexistence between Pakistanis of various ethnicities and whites in a small, unnamed town in England, author Nadeem Aslam, who was born in Pakistan and moved to England at the age of fourteen, constructs an original plot in which he prefers to give more space to the psychology of the characters than to the action.

From the very first chapters I found myself immersed in a kind of puzzle in which slowly each character's point of view brings to light the terrible truths and unmentionable emotions that lie behind the seemingly normal lives of women and men who live in a neighborhood populated mostly by Pakistani immigrants, where gossip, backbiting, and lies reveal how hypocritical and cruel human beings can be, while the author also highlights the courage to defy convention and the love for family and children.

I think the maps that give the novel its title represent precisely the inner journeys of the characters who, through their ideas, memories of the past, reflections on the present, and conflicting feelings mingled with clues scattered here and there, lead the reader to understand not only what happened to Jugnu and Chanda, the two lovers who disappeared into thin air, but more importantly how their life choices or the behaviors of their relatives contributed to their alleged murder. Through a profound and engaging reflection on the values of the Islamic religion and the contrast with the apparent open-mindedness of western people, the author prompts the reader to question what is right or wrong, how faith can influence daily and social life, and how parents' beliefs can affect the lives of their children, creating an irremediable contrast and leading to a struggle for individual freedom.

The novel unfolds over the span of one year and is divided into four parts corresponding to the various seasons. In the first chapter, 56-year-old Shamas walks the streets of the neighborhood where he lives alone with his wife. Their two sons Ujala and Changar and youngest daughter Mah-Jabin are now grown up and have moved to London to follow their own path. Shamas is not a believer and fled Pakistan when the new government began hunting Communists in the 1960s. He wrote and published poetry as a young man and worked in British factories and farms during his years of exile. He describes Pakistan as a poor country, where the war, which began in 1919 against British rule, led to several massacres (such as the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre) that Shamas and his brother Jugnu were eyewitnesses to.

Pakistan is a poor country, a harsh and disastrously unjust land, its history a book full of sad stories, and life is a trial if not a punishment for most of the people born there: millions of its sons and daughters have managed to find footholds all around the globe in their search for livelihood and a semblance of dignity. Roaming the planet looking for solace, they’ve settled in small towns that make them feel smaller still, and in cities that have tall buildings and even taller loneliness.

Jugnu, Shamas’s brother, also decides to question the tenets of Islam. Shamas remembers that his brother, a lepidopterist by profession who worked around the world, also always believed more in science than in religion, and since he disappeared along with his girlfriend Chanda, with whom he cohabited in the house across the street from his own, Shamas wonders if he was not killed for his ideas. Considered by all to be a sinner who also led Chanda, the daughter of a Muslim who runs a grocery store, down the wrong path, Jugnu is condemned even by his sister-in-law.

-chris-boland.jpg)

With each passing day Shamas grieves over her disappearance, feeling more and more lonely. “There have been moments over the past few days when he has felt that it is he who has died and been buried — and he hears his own footsteps as though someone has come to find him and dig him out.”

Shamas' wife, Kaukab, appeared to me as one of the most controversial characters in the book. On the one hand, I felt sorry that she is a lonely woman, forced to live in a country where she feels humiliated and marginalized. On the other, I could not fully understand her behavior and was puzzled by some of the concepts she expresses during family dinners, where she often clashes with Jugnu and her children.

Kaukab is against progress, women's freedom, and a marriage that is based on love and not on imposition by the family. Convinced that she is always on the side of reason, she refuses, for example, to listen to her daughter's needs, criticizes her clothing, and goes so far as to accuse her of not going to London to study but to follow disreputable conduct with white boys. Kaukab sees England as a dirty country, where the dissolute customs of men corrupt the minds and bodies of young women. I felt pity and anger for the daughter, who even goes so far as to regard her mother as “the most dangerous animal she’ll ever have to confront.” It was only because of her father's more open-mindedness that Mah-Jabin had the freedom to wear Western-style clothes and study at the university.

I was shocked, moreover, when Kaukab's son Ujala accuses her of drugging his food with a bromide, is a chemical compound which doctors use as sedative or to treat some neurological or lung diseases, that the cleric of the mosque allegedly gave her, making her think it was salt, to bring him back to the straight and narrow path. As Ujala painfully explains during a dinner with Kaukab and his sister Mah-Jabin:

The holy man read special verses of the Koran over some powder and asked you to secretly mix it into your son’s food. 'With Allah’s help the child will be obedient within thirty days.’ It was a bromide, the thing they put in prisoners’ meals to lower their libido, to make them compliant. That was when I left.

I also felt compassion for Kaukab. I realized that her behavior does not stem from selfishness or wickedness, but only from her different education. The daughter of a cleric, she was born and bred in a mosque and her father educated her to believe blindly in the Islamic precepts.

She had had no schooling beyond the age of eleven, but when she arrived in England all those years ago, bright with optimism, she had told Shamas she planned to enrol in an English-learning course. […] She never did take that language course. But when they bought a television in the 1970s — it was a Philips because her father had owned a radio made by that company back in Pakistan so she found it a reassurance and also knew it could be trusted — she began to watch children’s programmes with her children, but each one of the three moved on eventually, leaving her and her rudimentary grasp of English behind.

She was also taught to obey her husband, not to protest and to trust the word of the Koran and the Prophet Muhammad. Kaukab indulges in her faith and principles because she never learned to react to her condition and never had the means to be free. That is why she tells her daughter, "Not everyone has the freedom to walk away from a way of life. I didn't have the freedom to give you that freedom." Kaukab rarely goes out, and the kitchen is one of the rooms where she spends most of her time. Her home is a safe haven from outside danger.

Everything is here in this house. Every beloved absence is present here. An oasis — albeit a haunted one — in the middle of the Desert of Loneliness. Out there, there was nothing but humiliation.

Her fear of the world around her drives her to reject habits or opinions that differ from her own, making her feel safe only within the domestic walls, which eventually become a prison that prevents her from accepting any change. This is why her husband begins to distance himself from her and seek consolation in his love for a young woman named Suraya, who embodies lost youth and the desire to escape from a life of loneliness and suffering.

Love is another key theme of the book. Women like Chanda and Suraja are often forced to return to Pakistan to marry the men chosen by their families who, although they turn out to be violent and alcoholic, become the absolute masters of their lives. Although Chanda has been divorced twice, she was eventually forced to return to England to help her parents in their store. It is here that she falls in love with Jugnu, choosing to move in with him, at the cost of being excluded from society. But since for Muslims, love outside marriage is forbidden, Chanda is seen as a woman who dared to defy her country's moral laws, becoming the victim of a terrible sentence. When her brothers are arrested on charges of murdering her and burning her body along with Jugnu's, the community does not take the victim's side, believing that she was the one who drove the brothers to want to punish her only because of her desire to be happy with the man she loves.

For this reason, the novel is a conscience-shaking book that leads one to reflect on the plight of women who, even today, are forced into obedience in the name of male superiority in a patriarchal society, who struggle against oppression and physical and psychological violence.

This is also a book that portrays the socio-cultural and political dynamics of Pakistan, its history and traditions. The author describes its landscapes, myths, legends, cities, and the problems that have always plagued this country, starting with the internal struggles between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs and ending with the war that led to the separation of Hindu-led East Pakistan from the rest of the country, which became the present independent state of Bangladesh.

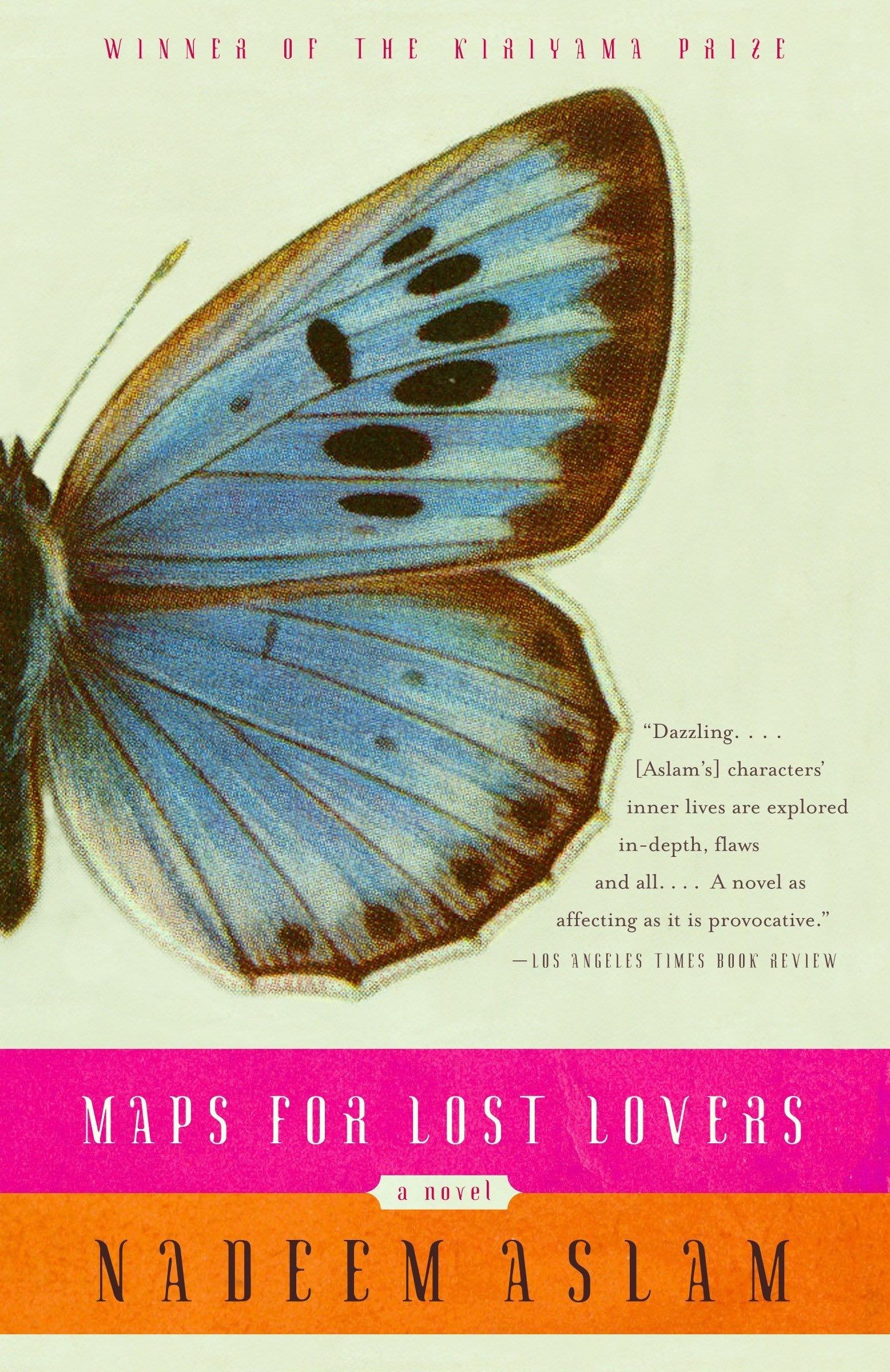

Although Aslam uses rather sophisticated language full of Pakistani terms, thanks to the highly evocative descriptions, which create an almost fairy-tale-like atmosphere, I felt as if I could taste the spicy foods prepared by Kaukab, smell the scents of the flowers and trees growing along the streets and in the gardens of the neighborhood, and admire the bright colors of the butterflies hovering around the lake. There is a lot of talk in the novel about moths and butterflies, not only because they are Jugnu's field of study, but because I think they perfectly embody a message the author wanted to send to the reader. The protagonists of this book, wrapped in a cocoon of pain, struggle with all their might to break out of a prison of unhappiness and loneliness, although sometimes this battle leads them to a tragic fate, because being themselves does not always lead to being truly free.

Nationality: Italian

First Language(s): Italian

Second Language(s):

English,

French,

Spanish

Supported by: