Published January 15th, 2021

Review

by Ailun Shi

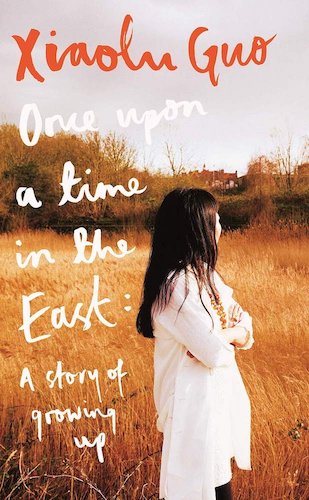

Xiaolu Guo in her memoir, Once Upon a Time in the East, writes an eye-opening tale to China's history framed in the gripping anecdotes of personal relationships and struggles. She puts faces and names to the people whose voices and stories were silenced, whether through illiteracy or censorship.

My friend and I got into a discussion a few weeks ago about "interesting" books. The definition of the word "interesting" itself is a little vague — is it supposed to be a deeply personal book? A thought-provoking book? Perhaps it's all of the above, and "interesting" feels a little different for everyone.

At the time, I admitted that I hadn't found any books to be truly interesting despite the countless books I'd read over the years. That is, until I read Once Upon a Time in the East: A Story of Growing Up by British-Chinese author and film-maker Xiaolu Guo.

What makes this book so compelling is that it isn't just a memoir of Xiaolu's life. It's also a memoir that steeps into her family's history and the immense changes China went through from the Cultural Revolution to the present day.

Xiaolu’s memoir spans from the beginning of her life to the period before she started writing the book. From the very start, Xiaolu throws us into the realities of her childhood: a newborn given away by her parents to a peasant couple to raise in a mountain village. She was barely two years when she was given away again, this time to her grandparents in Shitang, a fishing village. It wasn’t until age seven that she met her parents for the first time and moved to live with them and her older brother in the developing city of Wenling.

It’s in this beginning that Xiaolu sets up the heart-wrenching themes that run through her story: the feeling of loneliness, of never fitting in, being seen as worthless because of her gender, and the struggle of breaking free from those fates.

Although the book may be a memoir of Xiaolu’s life, the tale transcends generations, and the author does not shy away from recounting the harsh realities of those histories.

Xiaolu’s grandparents were both illiterate. Her grandfather was a failed fisherman and drunkard. Her grandmother came from a generation where foot binding was the norm. She never had a name of her own. She grew up being called “Second Sister.” When she was sold to Xiaolu’s grandfather at age twelve for a few bags of yam and rice, she was simply referred to as Guo Shi, or “Wife of Guo.” On the other hand, Xiaolu’s parents met in prison. Her mother was a Red Guard. Her father, an intellectual who spent time in a labor camp. The first time they met her mother beat and spat on her father.

Xiaolu’s descriptions of her family are a commentary to the norms of the times and the experiences shared among countless individuals and families that completely immersed me in China’s history. In between the anecdotes about her family, Xiaolu weaves in her own story and struggles. In Wenling, her mother and brother disliked and often beat her. She was constantly bullied by her teachers and students, and she was sexually abused, starting at age twelve.

But despite the struggles, or perhaps because of them, Xiaolu finds the energy and determination to seek her writing and film-making passions. She takes us on a journey beyond the ramshackle fishing village she grew up in and the factory-ridden city of Wenling. Xiaolu made it into Beijing Film Academy. She spent seven years studying film and literature, experiencing the underground art scene that fought to speak out against the government policies and censorship. From there, Xiaolu traveled even further when she won a scholarship to study in Britain. She eventually decided to stay there and committed to learning English, a completely new language to her.

Xiaolu’s words are bold and striking, and unerringly honest. She’s unafraid of using curse words to highlight the crude language used around her. She lays bare the upbringing she had under Communist China and highlights the commonplace abuses toward women that were still rampant despite the government’s reforms: drowning female babies because of the one-child policy, sexual assault, and domestic violence.

Her details and memories of specific conversations and thoughts are stark and frank, quickly enveloping me in the environments she found herself in. She painstakingly describes the self-hate she endured for not being able to fight back against her abusers, the loneliness of not belonging, and the dissatisfaction she had with the environment around her.

Despite the many places she lived, Xiaolu didn’t belong anywhere. She loathed Shitang for the years of poverty and hunger she endured there. Wenling was a reminder of the struggles she had with authority. Beijing was where she had to stifle her creativity to conform to censorship and the China Communist Party’s way of thinking. Even abroad, she was separate and different because of her background and her language barrier. Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder once said, “Home is where the heart is.” That wasn’t true for Xiaolu, who was often left behind in the romantic relationships she pursued and had no lasting affection for most of her family members.

Perhaps that's why I found the book so interesting — I found similarities in my life and my family's history to Xiaolu's story. I also resonated with her constant yearning to "be more" and rise above the life she was born into. The book is also an eye-opening tale to China's history framed in the gripping anecdotes of personal relationships and struggles rather than the cold and factual accounts of textbooks.

Once Upon a Time in the East is a must-read as it puts faces and names to the people whose voices and stories were silenced, whether through illiteracy or censorship. But even people who didn't grow up in China and never experienced the country or its culture can connect to Xiaolu's story of family, individualism, and balancing the two for self-creation. In essence, the book is about finding oneself and finding a place, whether physical or not, to call home.

Nationality: Chinese

First Language(s): Mandarin Chinese, Shanghainese

Second Language(s):

English,

Spanish

Supported by: