Published January 13th, 2025

Review

by Basudhara Roy

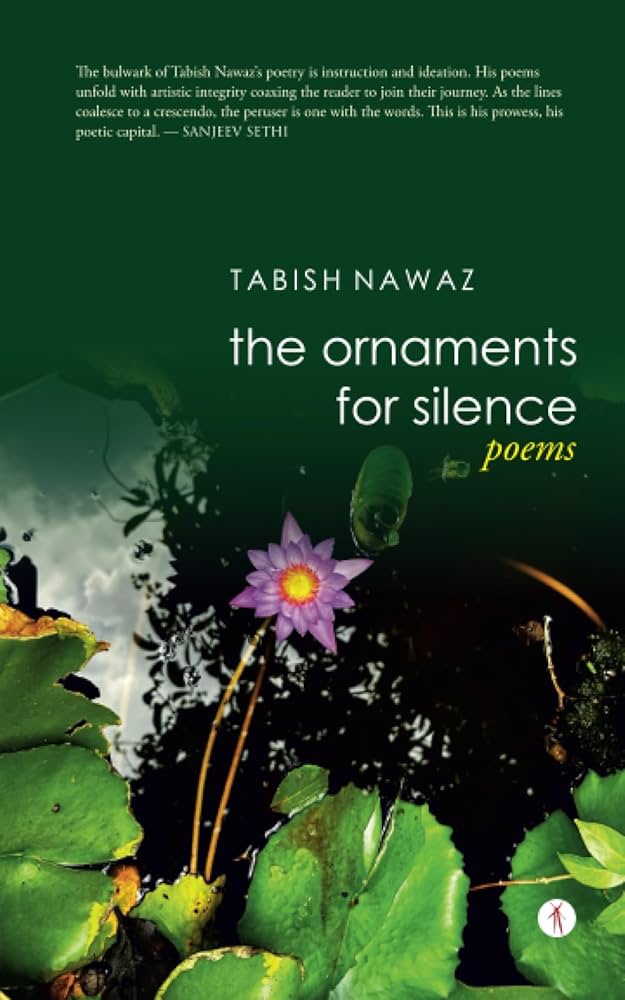

Tabish Nawaz hails from the state of Bihar in India and grew up in a multilingual community, avidly absorbing the linguistic and cultural repertoires of Urdu, Hindi and English. Educated via the medium of English in highly acclaimed institutions in India and abroad, it is this language that Tabish turns compulsively to, in fiction and poetry, to express his thoughts and concerns for the self and the world. His English is strongly marked by his cultural milieu as well as his firm academic moorings in the discipline of science. Tabish writes poetry with the eye of a poet-scientist and enters into emotional analysis with the lush precision that marks the Hindi and Urdu poetry of the Indian subcontinent. His debut collection, The Ornaments for Silence (Hawakal, 2023), showcases just that.

“Though the bough would come to you

without any of your doing but

you must try, to know

how useless trying is.”

(‘Organic’)

In the midst of the apocalypse of climate change and the corresponding destruction of the lexicons of mindfulness and love, can the search for silence within the hearts of words be a meaningful project? Tabish Nawaz believes it can.

One turns to poetry for, among other things, a quality of truth-telling that would be difficult to come by in prose. This has less to do with linguistic efficacy than with poetry’s potential to effectively harbour uncertainties and to hold life’s various paradoxes together with surrender and grace. In poetry, it is possible to accumulate and divest in such a way that both the ostentation and the penury of existence are laid bare. Good poetry is, forever perhaps, an aching after the right questions than a search for answers that will satisfy. It is an intensive investigation of the interstices of existence to discover what exactly is held and to evaluate if all of it is worth holding.

In The Ornaments for Silence, poetry sets out on precisely such an investigation. The title of the book lays claim to an expansive territory, that of silence. All that is not speech should be silence. But is silence merely an absence of speech, a non-speech? The preposition ‘for’ is telling here. The ornaments of silence might have denoted a descriptive cataloguing of silence’s beauty but the ornaments for silence, with its well-placed ambiguity, invites deeper interrogations. For the latter phrase, in contrast to the former, silence might not be a given. It could be a project under construction whose progress depends upon the availability of the right ornaments of speech. Might, then, the professed aim of these poems be the alchemizing of speech into silence, the journey from word to the dissipation of its need?

“In the collection, I have examined if language can speak our silence,” writes Tabish in his introduction to the volume. Articulating his sincere engagement with “mute vacancies in time,” he writes:

Would the words become mute in the process or deepen with meanings? Would they be able to return to their functional world, what would they haul back to the language from experiencing the muteness? Subsequently, I have touched upon the silence induced by the remembrance of the past, particularly the muteness induced by the failure of memories. How is that silence, when a memory becomes unshared, uncorroborated?

Deeply speculative, the 75 poems in this book engage with silence on a variety of planes. There is the silence of unspeakability, the silence of hostility, the silence of the amnesia of language, the silence of love, the silence of loss, the silence of wonder, and the mysterious silence of the universe as a whole. One finds here a ceaseless search for questions rather than answers. If speech and silence are two sides of the same coin of language, what questions will valuably reveal the underside of words?

This is a quest that consistently demands the interrogation of the strange within the familiar and has neither the need nor the capacity to accommodate what is truly unfamiliar or strange. In ‘Dear Soulmate,’ for instance, “Every separation is a death”; in ‘Metamorphosis,’ the heart is an iceberg “its tip visible like a bloody nose”; in ‘Nothing Survives,’ loves “trample each other”; and in ‘Let’s Wish Madness for Them,’ Time looks “for rescue / from its own patterns.” Each of these lines unsettles the reader in their own distinct way. Many of Tabish’s poems in this collection refuse to take the familiar for granted or to accept its comfort sans questioning, engendering a lexical sense of ‘unheimlich.’ “I become blank / with the question” states the speaker in the poem ‘Tinnitus,’ echoing auditory images of ‘bland’ and ‘blanche.’

Tabish’s language is sharp in its communication, his words agile and keen by turns. In a poem like ‘Education 101,’ for instance, the sharpness of language becomes an essential tool to deal with a thick-skinned subject, namely, the safety of women. The irony that women’s education in a distant city must begin by learning to deal with men’s physical aggression, is not lost on the reader — “If it comes to trusting men, you must first / have an agreement, but before you get into any, / make sure the blade is visible in your vocabulary.” Similarly, in the brief four-lined poem ‘Nationalism,’ the entire historical trauma of the partition and all contemporary national anxieties clearly surface in one single sentence — “Our country is shaped as a human, / shouldn’t that make us more?”

And yet, sharp as Tabish’s language is, it does not forego the sense of profundity that is called upon by words to bear the weight of thought. His language can, at times, surprise us with its density and its capacity to illuminate. In ‘The Oozing of Being,’ “A canopy of clouds covers the day / as one would protect the harvest / of desires from one’s own doing.” In ‘Morning Prayer,’ another piece of cloud “ascends the day’s back / like a child” while in ‘Inside Out,’ a flock of herons “lay crumpled like my many incomplete letters.” In ‘Multiplicity,’ “Colour is a failure of mixing. / We witness what is rejected, / what is unseen helps us see.” This last statement, as one would notice, affirms a well-known scientific fact, namely, that an object appears to be the colour of the light that it reflects. And yet, in Tabish’s enunciation, the matter of science becomes animated with the spirit of poetry, decisively enriching both.

An unflinchingly honest encounter with ‘self’ and ‘other’ is the essential scaffolding of each poem in The Ornaments for Silence as it attempts to open a door towards wisdom beyond itself. The subject of these poems is, largely, the ‘self’ as it witnesses and experiences itself through the medium of the ‘other.’ The ‘other,’ for Tabish, includes the intimate human world around him of family, relatives, friends, and lovers but most importantly, that of nature. His city, the city of Mumbai, features frequently in these poems as direct or indirect addresses to a world that abounds in nature’s bounty and sagacity. Nature manifests itself as a living, breathing presence in much of Tabish’s poetry, an essential co-actor in life’s ceaseless performance.

A deep philosophical awareness of ‘being’ saturates this collection as the poems attempt to place themselves between the real and the possible, the experience and the dream, and the hypothesis and the conclusion. The most ordinary moments of engaged living become, for Tabish, a site of acute observation and introspection. He often allows his poems to ponder, self-reflexively, on the question of language and the means of framing or constructing a more empowered natural world through it. In fact, in his best poems, concerns of nature and language come together inextricably and with a poetic wholesomeness that would be difficult to dismiss. In ‘Drudgery,’ words, pages, and streams fuse together in an unchallengeable sisterhood; in ‘Spectacle,’ the dry earth becomes “a fable of footprints forms”; in ‘A Few Questions,’ words that lose themselves in the desert are invoked to life again, to “the greenery of expressions.”

These endeavours, then, of letting language be led by nature constitute perhaps the essential “ornaments for silence.” The privileging of silence over speech and the examination of speech with a view to either uncover or to imbue it with silence is vital towards the engendering of a new aesthetics of communication and survival. In the midst of the apocalypse of climate change and the corresponding destruction of the lexicons of mindfulness and love, the search for silence within the hearts of words becomes an act of restoration, both of nature and of human civilisation in its arms.

“Tabish Nawaz emerges in this opening collection as a poet of many promises,” writes well-known critic Anisur Rahman in his foreword to the volume, and any reader of the book will robustly nod in assent. There is a sincerity in these poems that penetrates much of the din of modern living to find a place of and for silence. Here is the exploration of and a call for a new syntax of being — one which takes into consideration not only that which is repetitively said but so much of what remains unspeakable and unsaid. The environmental scientist in Tabish clearly aids the poet in his observation while the poet in him adds depth and value to the scientist’s vision. Between the two, the reader witnesses a restrained glory — the serenity of rapture combined with the adherence to logic and the surrender to a form of knowledge that lies beyond rational comprehension.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Bengali

Second Language(s):

Hindi,

English

Supported by: