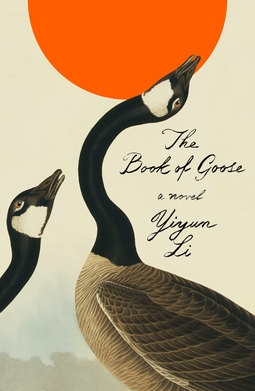

Published January 8th, 2024

Review

by Samiksha Tulika Ransom

A month ago, I happened to chance upon Yiyun Li’s interview in the Bad Form review, where she talks about her ‘aha! moment’ for The Book of Goose (2022). Though the book is primarily set in the French countryside, in the interview, Li states that she did not have to go to France to write it. I had been looking to read such a book for a long time since this was close to what I incline towards in my own writing — self-sufficient characters with little external or overtly evident characteristics, who live mostly in their head. Such characters could be an everyman or an everywoman. So, when I read the interview, I knew I absolutely had to read the book!

The Book of Goose did not disappoint. In fact, it turned out to be rather extraordinary. I’d ascribe its ‘wow factor’ primarily to two techniques of craft. First, Li’s characters are strong and self-sufficient. They’re able to carry the entire weight of the story by themselves. Yet, Li still decides to root them loosely in the setting, in a manner that is important to their inner world and state of being, and which imparts to the book its dreaminess. Since the characters are loosely rooted in the setting, they do possess an individuality and yet they could be anybody — even you or me. Second, Li’s work possesses a unique subversive quality, whose execution is subtle and quite unlike other works that employ subversion. It is neither dystopia, nor utopia, and yet a subversion of the “real world” — a term intrinsic to the story.

-cc-by-nc-nd.jpg)

The Book of Goose is phenomenal and full of surprises. The first of these is its beautiful one-of-a-kind morbidity and a philosophical dimension that does not characterise much of the fiction of our time. Li unfolds the account of two thirteen-year-old French girls, Agnès and Fabienne, who lead routine and somewhat boring lives in the French countryside. Their days are made up of household chores and minor errands like grazing the cattle. These girls, growing up in the backdrop of war, extreme poverty, the death of their siblings, and their parents’ indifference, have had their fair share of trouble in life. Yet, unlike their parents, pain is not everything to them, and they seem to not pay too much attention to it. They have a life of their own. Together they lie on graves in the cemetery and adore the silence around them. Together they break the silence with the ‘games’ they make up and play against the world — “the real world” as they call it, as they constantly try to defy it. Together they discuss the inadequacies of men and brood on strange and deep philosophical matters — could they grow happiness like apples and oranges?

Usually Fabienne, the dominant one in their friendship, breaks the silence and Agnès follows her lead, asking her questions, and simultaneously ensuring that Fabienne stays in her authoritative role. In Fabienne’s words, she “makes things happen for both.” In this, both are pleased. Life goes on normally until Fabianne tells Agnès that they’re going to play a new game: They’re going to write a book. Of course, Agnès, being Fabienne’s ‘yes-girl’, writes down the stories Fabienne makes up. With the help of the village postmaster, M. Devaux, Agnès and Fabienne are even able to get the book published. The book takes the world by storm, but there is one catch: Fabienne declares that Agnès alone must be considered the author of the book in the eyes of the world — a secret they keep from the world.

While Agnès writes pretty well herself, she is not the author of the book that the world believes she has written, and yet she does not protest when Fabienne makes that demand. Moreover, she reaps all the benefits due to being identified as the author — frequent visits to Paris, getting photographed by expensive photographers, receiving fanmail, and getting to spend a year at Mrs Townsend’s school in England, fully sponsored. But is Agnès happy? No. Is Fabienne jealous? Hardly. These girls see beyond the real world and beyond what the people of the real world see, both of which are characterised by a suffocating quality that they find repulsive.

The Book of Goose is an enchanting tale of friendship, coming of age, love, and loss. Yet, love is not lost between Agnès and Fabienne for reasons dictated by the real world and they do not part as people of the world do. There is no betrayal, no crimes are committed that are born of greed, there are no extravagant desires, no boy-trouble, no jealousy between them. Their secret is safe, and yet the real world, against which Agnès and Fabienne have devised all their lives and sought to earnestly defy every day, hour and minute, catches up to them. Will Agnès and Fabienne turn victims?

If Agnès and Fabienne do not want fame, the title of ‘author’, trips to Paris and England, fancy soaps, dresses, and the company of elite people, what do they want? Why are they so eager to choose a life of anonymity and life-long poverty? Are they making the biggest mistakes of their lives when they decide to throw away all the pleasures of the real world? What are their true desires? What else could the world have offered? Or are they simply just foolish?

The Book of Goose is no ordinary book. It haunts the reader even when they’ve finished reading it. The more one reads, the broader one’s vision becomes, and the more one understands Agnès and Fabienne, forgives their little acts of indecency and rebellion, and empathises with them as people not very different from themselves. One understands that Agnès and Fabienne, if compared to the world, aren’t truly morbid, or even foolish for that matter. What they desire is to repudiate the world they inhabit and create their own, where their existence — their very living and breathing — is a refutation of the world and its ways. Their life in the French countryside, lived in poverty, lack of sophistication, and little fun, is just as valid as any other life. It is one way to exist, yet another way of being in the world. The Book of Goose is an unforgettable tale of overcoming the world, perhaps in the only way in which it can be overcome: by creating a world of one’s own, for as long as one can.

Nationality: Indian

First Language(s): Hindi

Second Language(s):

English

Supported by: