Essay

by Selene Lacayo

Time is an odd thing. You really can’t grasp how much of it has passed until you are confronted with a photograph of a former you. Cross-referencing that image with the one mimicking you in the mirror, you realize the way in which time has settled in your skin in the form of more pronounced creases around your smile.

Over a decade had established itself in my husband’s face when, after obtaining two degrees in the U.S., oceans away from the Lebanon of his childhood, our permanent residency papers arrived. Our Green Card had finally made its way to us after we had married, began our careers, bought our first home, and became parents twice.

Through all of those important moments in Jad’s life, his mother and siblings had been distant spectators of his growth and transformation. Like many of us who immigrate to a different country, Jad had learned to numb the parts of his heart which ached with homesickness. He too watched his immediate family change and grow from a distance, through the photographs we used to receive. There was one of Fares and Laila, Jad’s nephew and niece, being part of the Palm Sunday procession in church. Laila wore a long white dress and Fares a crisp cream-color shirt and dark dress pants. Both of them held the candles they had decorated for the occasion with olive tree branches, ribbons, and flowers. Their smiles were a mix between solemnity and happiness. His sister Jolie stood proudly behind them; her obsidian color hair framed her face.

When we started dating as two penny-pinching college students filled with dreams, I learned about Jad’s closeness to his family through anecdotes and the summary of his calls with his mom, interpreted after the fact into English for me. When we got engaged, I knew I was gaining a whole other family, if only on paper. We had never met. I only knew the way their eyes spoke to me from static photographs. The only real relationship between the family I was acquiring and myself was limited to knowing the sound of their voices. The arrival of our Green Cards, a decade after we each had come to be in the U.S. and three and a half years after our application, presented the opportunity to remedy that. We were now free to travel outside the U.S. without fear of being denied re-entry.

❊

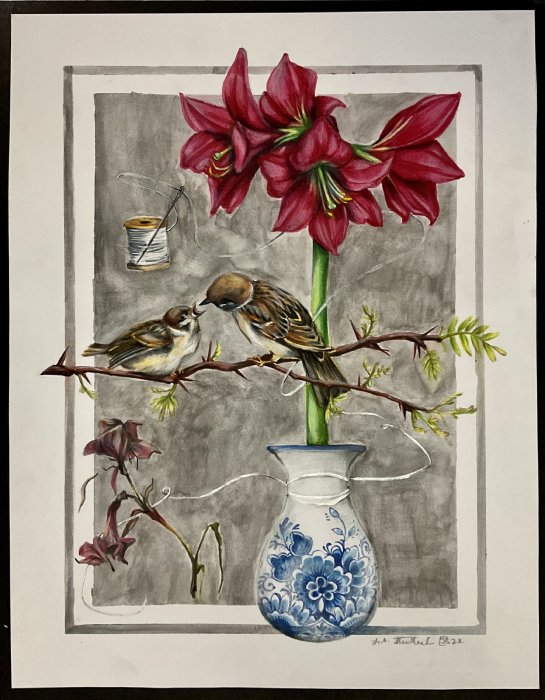

Drawing with light. That is what photography means from the Greek photos (light), and graphia (writing or drawing). It is usually the moments that bring us light that we photograph. The ones that are dearest to us and we want to keep close to our hearts. Photographs are collections of moments waiting to be experienced again and again when we gaze upon them. They are placeholders for our loved ones in our memory.

In the era of digital photography and social media, it is perhaps silly to think about carrying printed photographs along as you move through life. However, when I arrived in Michigan in 2002, I wanted to bring printed photographs of my parents, my brothers, and my best friends. They were not mere dorm room decorations, but my companions. Their presence was a squalid substitute for their hugs, acting as a band-aid for my homesickness.

The photo with my closest high school friends, Inés and Verónica, never failed to take me back to times of change, reminding me of how the three of us sort through them together. Our bright, wide smiles announced to the world that we were ready for whatever was to come.

We had all been accepted into foreign universities and had left home at the same time. Looking straight at the camera, we didn’t hide the pride we felt for one another. That photo was proof that our sisterhood was strong.

Jad and I got to know each other in the company of taciturn photographs that talked about our pasts in fragments. They were the carriers of warmth, love, and a different version of us.

❊

I don’t remember when I started going with my mom to the cream house with chocolate brown garage doors. What I do remember is being very little the first time I tried a fig from the tree growing in the house’s yard. This was something notable, even at a young age, because figs were not the kind of fruit readily available fresh in Mexican markets.

The purple fruits were not the only peculiarities of this house, it was also unusually decorated. My eyes were drawn to the small glasses with ornate golden rims that surrounded a metallic coffee pot of the same color. They were encased behind the shiny glass of the buffet in the dining room. The pot was different than others I had seen. It looked like a metallic cup and had a very long handle. An assortment of expensive cut glass pitchers and champagne flutes, as well as many silver little spoons and other serving utensils kept them company.

The walls had a few carvings of cedar trees made of wood, as well as paintings of mountainous landscapes by the Mediterranean Sea, tying the family directly to their homeland. An image of Saint Charbel, the patron saint of Lebanon, with his long and gray beard, looked over the sitting room guests. The owner of the house, and grandma of my playmate, also had something different about her — at least different from other grandmas I knew. She always wore makeup with a heavy line of jet black kajal highlighting her almond-shaped eyes. She used many bracelets that jingled together as she talked expressively with her hands, and always dressed in bright colors and gold.

Licha Grayeb, the matriarch of the family, had been a close friend of my maternal grandmother before she moved to Guadalajara, where I grew up. My mom would take us to her house so that she could sip Turkish coffee from small cups and talk about grown up stuff, while we played with Licha’s grandson who lived next door. In her house I tried grape leaves stuffed with rice and ground beef, kibbe, hummus, rice with noodles, and “fingers of the bride.” The translation from Arabic of these delicious rolls of phyllo dough with nuts, honey and butter, doesn’t do any justice to the delicate dessert that melted in my mouth, dissolving any childhood worries automatically.

My discovery of all the marvels contained in just one house continued as I grew; soon I understood the reason why Licha’s words sometimes didn’t have the proper “r” sound in Spanish. Behind the ever-present smell of cinnamon and garlic in her kitchen, was the fact that she was Lebanese. Licha’s family had emigrated to Mexico from the country of the tall cedars. She and her husband Felix had met when both of them were already in their host country thanks to the tightly knitted connections that the Lebanese community continues to have even today. They made a life among the similar values of Mexican society, which put family at the center of everything.

When I was at that age of asking endless questions, I learned that the restaurant with the delicious Sunday buffet that the whole family adored served Lebanese food. I also learned that many of the names of big commerce around town, like car dealerships, were Lebanese. Even my brother Dennis’ best friend since first grade was of Lebanese descent. The more I paid attention to Lebanese things, the more I saw them around our relations and the city in general, for Guadalajara is one of Mexico’s main places where Lebanese immigrants made their homes and their fortunes.

Limitations for growth and prosperity during the Ottoman Empire, propelled the immigration of more than one million Lebanese people to the Americas, mainly settling in the U.S., Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico between 1860 and 1914. Approximately five thousand of these immigrants settled in Mexico at the beginning of this influx. By the 1980s, Mexico had more than 100 thousand Lebanese, when taking into account third generation descendants. The Lebanese population grew in numbers thanks to the welcoming immigration policies at the end of the XIX century. Lebanese immigrants worked in agriculture and were great merchants. They instituted the concept of payment in installments in Mexico growing their businesses from seemingly nothing more than their charm and hard work. They became titans of the textile industry. The influx slowed down after Lebanon became an independent country in 1943, limited only to family members who visited and stayed. However, it picked up again in the 1970s due to the many conflicts in the Middle East. Through the generations, what is curious is that Lebanese in Mexico have maintained their identity rather than being completely absorbed into the Mexican one.

I liked learning about Lebanon because of our friends, and their wonderful food and fig trees. I also liked knowing who people referred to whenever they said that many in my family looked Lebanese. The long noses, thick eyebrows and curly eyelashes, the almond-shaped eyes, and the olive skin tone were all present starting with my maternal grandpa and his siblings; ending with my brothers and I. Our ancestors had come from Spain and our features were proof of our Moorish and Phoenician blood. Both groups lived at different points of history in the Iberian Peninsula, now Spain and Portugal. Of these groups, the Phoenicians are tightly connected to modern day Lebanon for it is from the coast of this Mediterranean country that these sailor merchants traveled the world.

Lebanon and I already had a relationship from my early childhood, what I didn’t suspect was that it would become a main agent for growth and change in my life.

❊

Portraiture is an art form dating back at least to ancient Egypt (5,000 years ago). Ever since then, portraits have been used as a way to remember someone by recording their appearance. Paintings, sculptures, and drawings were the only ways to make portraits until photography came along.

What started as a highly expensive process only done by professionals in the early 19th century, was brought to the masses by the beginning of the 20th century with the invention of Kodak’s brownies. It was thanks to these portable cameras that photography expanded from portraiture, landscapes, and buildings, to snapshots and casual activities. By the end of the 20th century, image control SLRs, point-and-shoot cameras, and digital technology made documenting life’s moments so easy that carrying a photo album or even reproducing it was something that most anyone could afford.

Photographs tell stories of exploration and discovery, sorrow and war, love and kindness. They are a very important way to take all that matters to us wherever we go. They are a way to open a window into our past for those who are getting to know us.

❊

During a video call with Jad’s mom as newlyweds, my now official mother-in-law, Josephine, showed me how she had printed a photo of me in my wedding gown. She had placed it in her living room alongside the photo of her daughter, Jolie, on her wedding day. Since we had not met in person before, and didn’t have a language in common, that gesture was her way of welcoming me into the family.

I imagined Josephine studying our wedding photos searching for sparkles of happiness in her son. Wondering who was the couple acting as Jad’s parents at the religious ceremony, hoping that he felt her presence there. In the same fashion, I studied photos of Jad’s family every time we received new ones. There was one in particular that captured my heart from the beginning. It was of little Fares when he was about three. Half of his body peeked through a window of Josephine’s home to pet a cat stretching by him. I imagined the small boy’s laughter accompanying the frozen smile on the photo, and I wondered if he would like us when he finally got to meet us in person.

I also thought of Jad as a boy growing up in that stone house. Eating grapes from the

vines on the arches of the carport. Learning to ride the bike his uncles gifted him for one of his earliest birthdays. Helping his mother set a proper Lebanese mezze on the table for parties and special visitors. I pictured him running up and down the pebbled stone hills, calling his friends

from the houses with orange tiles that made up his town. All these images floated in my mind as I connected photos and videos of Jad’s past to the anecdotes he trusted me with from the very beginning of our friendship.

As I sat playing with my children in Jolie’s living room, I thought about how surprised Jad would be to find people have changed and streets have multiplied. I had experienced a version of this gradually every year when I visited Mexico since I had left it for good. I could not anticipate the massiveness of the feelings that would engulf Jad after more than a decade of not walking the streets of his childhood. After all those years away, I was about to live Jad’s shock as he would be reconciling our multicultural life in the U.S. with the life he had left behind in the Lebanon of his childhood.

Jad and his siblings, Elie and Jolie, deliberated in Jolie’s kitchen about whether to tell Josephine that we had arrived in Lebanon. I for my part did not want to surprise her. Lebanon, often in the list of places not to travel to by the U.S. State Department, had been a country on our list to visit since our engagement became official more than six years before. Lack of funding, immigration paperwork, and the limitations on travel had not allowed for me to travel and meet Jad’s family and for him to reunite with them. There were too many emotions bottled inside all of us for them to explode at once like pyrotechnics.

Nobody listened to my concern.

I sat shotgun along Elie in the gray Montero making its way from Zahle to Rachaya about 45kms away. Images of the Bekka Valley inundated my view. The arid landscape of the valley in the intense August heat, showcased buildings and land in sepia. Just like old photographs, the view surrounding me was meant to evoke the feelings of longing to learn about someone’s past. There were trees and bushes sprinkled around; just like I had seen in so many of the Bible stories of my childhood that we used to color at school. The occasional shepherd herding sheep made the image even more vivid.

We entered the hilly town with the stars accompanying us in our journey up Mount Hermon to the family house where Josephine was unsuspectingly waiting for Elie to arrive with Jolie’s children. That was the excuse given to him over the phone so that he would head to Zahle earlier. I could only see the shadows of stone houses and trees. No colors were present other than blues and grays and the occasional orange of the tile roofs that the streetlamps would let me perceive through the darkness around us.

We were moving slowly through the slender pebbled streets and my heart could only take so much more of the excitement bubbling up under my skin. I had my phone ready to record the highly anticipated reunion. Images would immortalize the moment in which mother and son finally reunite after more than a decade of relying on phone lines and frozen moments in photographs. My hands were shaking when at last we arrived at the house and started inching closer and closer through the driveway.

Josephine sat there, relaxing after a long day of cheesemaking, sipping mate with the neighbors. Blinded by the headlights, she could only make out the silhouette of the car, until we got close enough for her to recognize me in the passenger seat. Her face ecstatic at the sight, her tears streaming down her face as her arms raised in the air while she ran towards the back seat where Jad awaited her, flanked by our children.

Behind the phone documenting the encounter, I let out all the tears that I had been holding onto since our arrival to Lebanon only about 24 hours earlier. They were reserved for this moment, for when time stopped for a second while Josephine launched herself into the most powerful embrace that I had witnessed in my whole life. The light of her happiness drew images of timeless love on the surface of our future nostalgia.

My phone shot the images that would be the faithful witnesses of the type of happiness that only people who have lived to miss someone in another part of the world can understand. She wrapped Jad in her arms while looking right into his eyes in disbelief, kissing his wet face with no reserve.

Jad had come home.

Appeared in Issue Fall '23

Nationality: Mexican

First Language(s): Spanish

Second Language(s):

English, French, Italian

U.S. Embassy Vienna

Listen to Selene Lacayo reading "Lebanon".

To listen to the full length recording, support us with one coffee on Ko-fi and send us an e-mail indicating the title you'd like to unlock, or unlock all recordings with a subscription on Patreon!

Supported by: